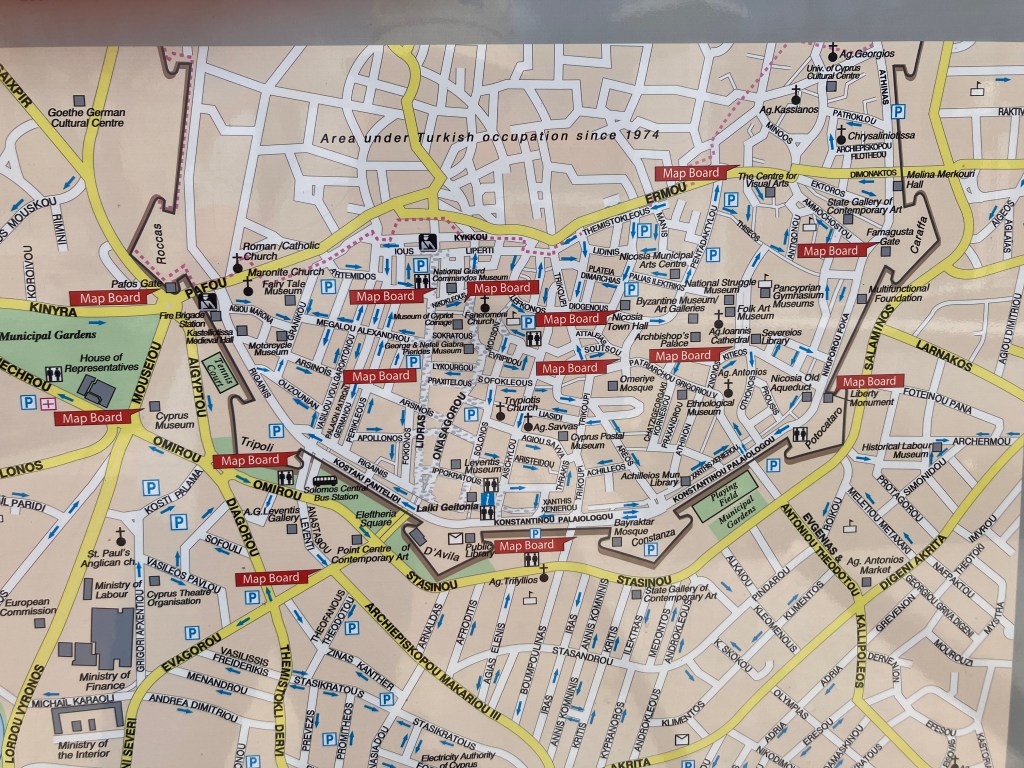

Nicosia is the capital of Cyprus, established thousands of years ago. The historic city is a fortification, shaped as a circle with 11 triangular bastions and a moat around, as built by the Venetians during the Renaissance. The city is divided in half with Greek Cypriots living to the south and Turkish Cypriots living to the north. A neutral zone, manned by the UN peace keeping forces, runs in the middle. Below are my reflections on a few of the important sites I visited, including stretches along the border walls and the National Struggles Museums on each side.

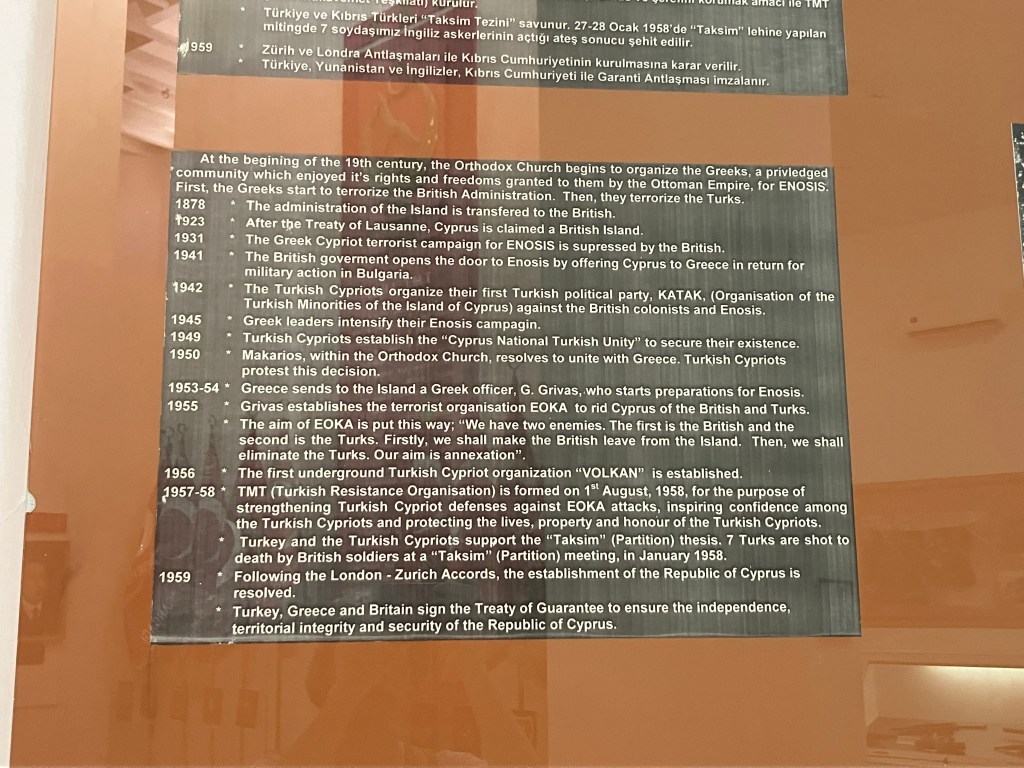

The displays of both National Struggles museums are vivid and provocative. Images are graphic and shocking, whereas information is organised around overarching National ideas of identity, injustice and rights to the island. The content appears to gravitate towards the respective side’s losses and presence in Cyprus, but does not refute the other side’s information. The Greek exposition majors on the results of the 1950’s referendum for Enosis (union with Greece), whilst the Turkish one prioritises a later agreement where the island’s division was agreed upon. Three centuries of Ottoman rule are seen as a period of stagnation on the Greek side yet a time of peaceful cohabitation on the Turkish side.

Expositions describe different phases of the island’s main inter-ethnic conflict of the 20th century. Turkish side’s images show more of Greek violence towards the Turks in the 1960s-1970s, whereas the Greek displays focus on the British violence towards the Greeks in the late 1950s. Being a British colony for the larger part of the 20th century was one of the obstacles to the peaceful cohabitation of the island’s two dominant ethnic groups, according to Calame et al (2009).

Along the physical division lines, the situation is quite different between Nicosia’s halves. On the Greek side, one sees abandoned ruins and quiet residential streets running along and into the concrete-filled barrels and police posts. On the Turkish side, there are buzzing businesses, such as car repair and woodwork workshops or retail alleys, interspersed with barbed wire gates. Sinir Parki within one of the fort’s corner bastions on the Turkish side is a fascinating point: previously closed for the public as part of the neutral zone, the park is now a lively and prominent public place, with views of the city’s other half behind a barbed wire.

Crossing from one side to the other at the check point is quick and hassle-free. From my experience of nerve-racking borders between Poland and Russian Kaliningrad region, or Lithuania and Belarus, this is as peaceful as a EU land border could get. Seeing the border officers carry out their duties as a mere formality made me wonder if the division is a relic of the past which no longer provokes apathy to the other side in ordinary people. Reading about Greek and Turkish Cypriots peacefully cohabiting elsewhere in the world (Calame et al., 2009) and not seeing a single ‘peace-keeper’ in the neutral zone reinforced this thought. A temporary line sketched with a green pencil became a rigorous masterplanning weapon for dividing buildings, streets, communities and institutions. Would there be more conflict if the segregation was to stop?

Reference:

Calame, Jon, et al. Divided Cities: Belfast, Beirut, Jerusalem, Mostar, and Nicosia. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt3fhdcs. Accessed 3 May 2023.