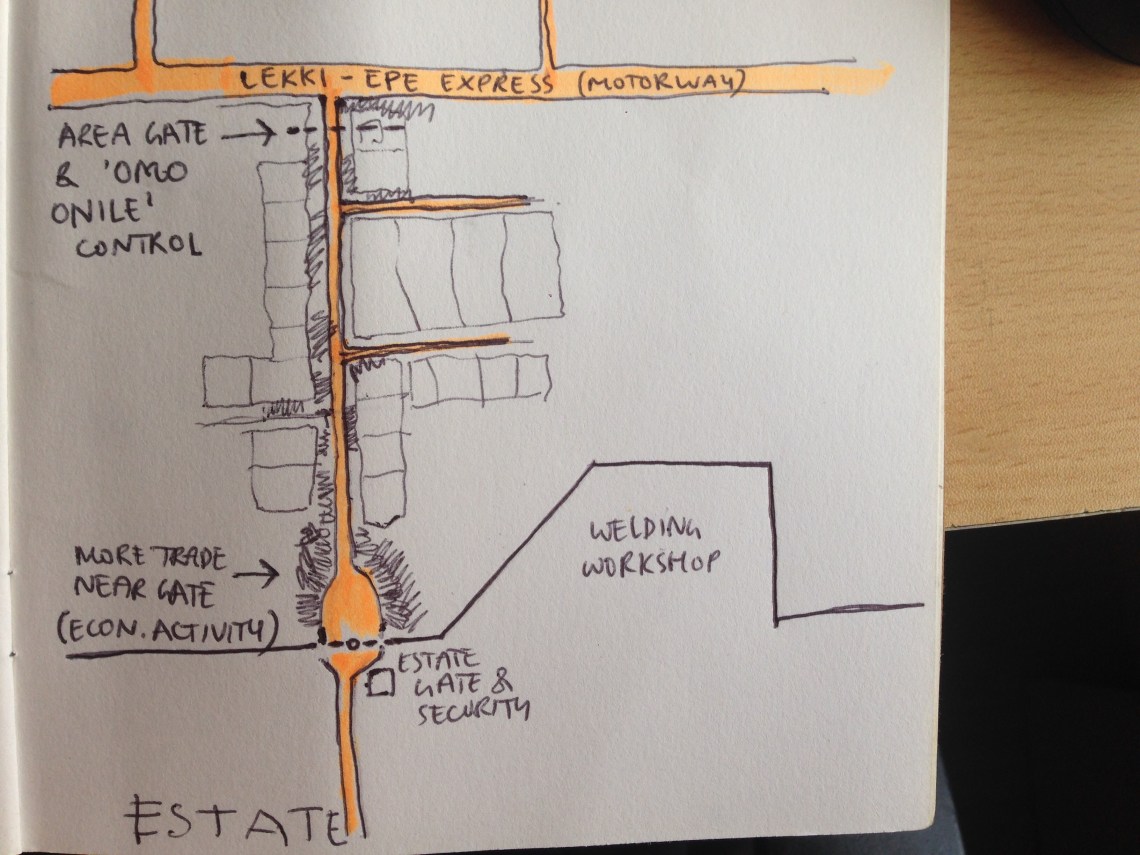

My previous post describes a stretch between the Lekki motorway and a typical gated estate. Such zones populated by private houses, places of worship, schools, shopping malls and occasional offices have different layers of local regulation.

Regulation

Oba (chief) or area’s indigenous community has the right to the land. People working for Oba or indigenous guys, Omo Onile, sit at the entrance to the territory and charge taxes for commercial activities, land purchases and any construction works. The charges are imposed on estate developers (who save their residents from much of the process) or on the individuals/businesses operating within the public (non-estate) zone of the area.

Below: scene I witnessed of spikes brought under a constrction truck, whose driver was refusing to pay for entering the territory for commercial purpose.

Below: Chief’s palace under construction

Below: motorbikes and other commercial transport taxed by an indigenous group along a residential Lekki road.

Roads.

People like good roads. Roads get damaged quickly during construction periods and become subject of disputes. I have witnessed a local community which positioned some ‘guards’ along good new stretches of a road to regulate any entry to these, particularly by commercial vehicles.

I have also taken a road which was previously well made, however was purpusfully destroyed by some local individuals who were expecting to be payed for making it good afterwards. The road still remains in poor state: photo below.

Drainage

Unlike in the residents of some gated estates, individuals living in the public zone need to maintain and organise the amenities (in place of faulty municipal ones) for themselves: these include water, sewage, electricity and street drainage, which, if clogged up causes severe street flooding zones during the rainy season (May, June).